THERE is something repulsively fascinating about a snake which will always make "snake-charming," as a public amusement, an acceptable entertainment. Of course, a great deal of the attraction lies in the association of danger, but I am convinced that in no small degree it may also be ascribed to the instinctive revulsion of feeling which most people cannot repress at the sight of a reptile.

The common prejudice in favour of using feet as a means of progression is not to be dated from the "Trilby " craze. The mere fact that the Enemy of Mankind is referred to as a serpent in the very earliest historical records sufficiently indicates that in man there has always been a certain inherent loathing of snakes and other go-by-grounds.

When therefore we see, in public exhibitions, men, women, and even children winding snakes of

many varieties around them with a fearless familiarity, the first thought that occurs to the spectator is one of

astonishment that the performer can bring himself to " touch" them.

When therefore we see, in public exhibitions, men, women, and even children winding snakes of

many varieties around them with a fearless familiarity, the first thought that occurs to the spectator is one of

astonishment that the performer can bring himself to " touch" them.

The repugnance which one not unnaturally feels towards snakes is, however, insignificant: as compared with the danger which the performer runs in placing himself at the mercy of a number of reptiles, the least of which would be able to destroy him.

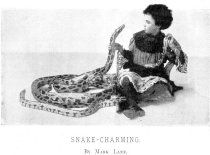

In the photographs which accompany this article the dangerous experiments which constitute a snake-charmer's performance are very accurately represented. Captain DeVoy and his little daughter, Lottie, who is but eleven years of age, kindly consented to reproduce the items of an entire performance, so that we might secure this series of interesting photographs for the benefit of the readers of this magazine; and they may be accepted as accurately depicting the exact perflormance which the father and daughter are at present giving at various places of public amusement throughout the country.

The pictures acquire an added interest from the association of a child with such an entertainment; and it is

interesting to note that not only has Captain De Voy's daughter no fear of her weird playmates, but she actually

enjoys the performance which enables her to fondle them.

The pictures acquire an added interest from the association of a child with such an entertainment; and it is

interesting to note that not only has Captain De Voy's daughter no fear of her weird playmates, but she actually

enjoys the performance which enables her to fondle them.

Captain De Voy has been associated with these entertainments for nearly sixteen years. His wife was a well-known snake-charmer under the stage name Mlle. Onzalu, and for her he used to tame and train the snakes before she performed with them. The particulars given in this article have been furnished by Captain De Voy, who very frankly and courteously consented to afford me every information in his power.

Many people have the impression that snakes, before being used by a snake-charmer in performance, are drugged, or by some other means rendered harmless. This, however, is quite a mistake. The snake-charmer who wants to make a purchase for the purposes of his performance goes to Jamrach's, or some other well-known emporium, and handles the snake he fancies, there and then, exactly as it has arrived in its wild untamed condition.

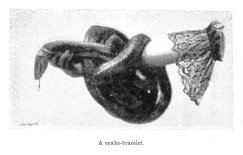

The "knack" of snake manipulation is to catch the reptile by the head and the tail. By holding the head the snake is

unable to bite, and unless the tail is free, it is unable to exert its powers of crushing. The snake-charmer in these

earlier stages of acquaintanceship also adopts the precaution of wearing stout leather gloves.

The "knack" of snake manipulation is to catch the reptile by the head and the tail. By holding the head the snake is

unable to bite, and unless the tail is free, it is unable to exert its powers of crushing. The snake-charmer in these

earlier stages of acquaintanceship also adopts the precaution of wearing stout leather gloves.

Snakes in captivity evince much intelligence, and their tameness is in no small degree a lively sense of favours to come. They soon appear to realise that from their trainer alone is to be expected not only food, but what is in more constant request, the warmth which is essential to their existence. They must be kept in a temperature of from 70o to 80o, and this is effected by wrapping them in blankets surrounded by hot-water pipes.

Their feeding is a leisurely process, as there is an interval of four weeks between each meal! In a natural state the interval is a much lengthier one, but then the meal is vulgarised into a veritable gorge.

The etiquette -- or the exigencies -- of a professional career causes the snake to approximate to more civilised habits. But the snake even in its tamed state is never civilised to the point of appreciation of prepared food, and insists on a menu of live rabbits, rats, mice, or fowl.

These it eyes with a critical glitter, and then having bestowed on them a crushing embrace, he swallows them whole; but he would lie beside the best efforts of a Parisian chef and starve.

Captain De Voy's collection may be regarded as a fairly representative one, and it consists of an Indian boa,

The taming process is commenced by the gloved grasp of the head and tail. The snake seems to realise at this stage that it is in the hands of a master, and when later it understands that no harm is intended and that certain kindness may be looked for, it speedily becomes tractable. Captain De Voy's snakes are all distinguished by names, and most of them answer to them with readiness.

But it is not every snake which responds to the requirements of the trainer. Some remain intractable, and can never be depended on. It was only about three weeks before these photographs were taken that Captain De Voy was obliged to kill a valuable African harlequin snake, 11ft. in length.

He had spent a considerable time in the endeavour to tame and train it, but without much success. The harlequin was evidently not stage-struck, and resolutely refused to fall in with its trainer's views. In the main, too, it had the best of the argument, for a snake 11ft. in length has to be treated with diplomatic respect. After a time it appeared to be sufficiently tractable to be trained for use in his public performances, but while Captain De Voy was endeavouring to wind it round his body one day in the course of a private practice the harlequin suddenly became ferocious, and the trainer very narrowly escaped losing his life. Fortunately he had managed to retain his hold on its head, and before it could coil itself round his body to crush him he succeeded in killing it by throwing himself down and letting the whole weight of his body come on its head.

Losses such as these have to be reckoned with in the business of snake-charming, and as the price of snakes varies from 30s. to £20, or even £30, the risk is not an inconsiderable one.

There is also the danger of losing snakes through climatic disadvantages and diseases -- such as canker in the mouth -- to which they are peculiarly liable. To expose them to the cold, either by forgetting to renew the hot water, or by not providing them with sufficient blankets, might very easily prove fatal to the entire collection. But snakes, no matter how tame they may become, are always treacherous, and have to be very carefully watched at every performance. The performer, however, soon learns the temperament of each one, and can tell its mood by its hiss, which varies as its humour is good or bad.

The snake which happens to be in a bad humour is not excused its share in the night's performance -- to do this would be to invite a recurrence of its mutinous spirit -- but the performer generally exercises extreme prudence in dealing with a surly subject.

Not the least important item in the list of a snake-charmer's attainments is the ability to treat his reptiles medicinally. Captain De Voy's medicines are composed of olive oil, alum, blue-stone, copperas, borax, and honey. These ingredients he declares to be adequate for the treatment of all the ills a snake is heir to

His medicine-chest for the relief of a human being bitten by a snake contains but one antidote -- Irish whisky. This he always endeavours to keep in a state which would be viewed with disfavour by the Excise, viz.; 25 to 30 degrees over-proof. To saturate the wound externally, and the body internally with strong Irish whisky is, according to Captain De Voy, the only reliable cure for snake-bite.

I give his statement for whatever it may be worth.