PHAROS

THE

EGYPTIAN

BY GUY BOOTHBY.

Illustrated by JOHN H. BACON

| September | Contents | November |

Illustrated by JOHN H. BACON

| H |

From what I remember, and speaking at a guess, the passage could scarcely have been less than a hundred feet in length, and must have contained at least a dozen statues. At the farther end it opened into a smaller chamber or catacomb, in the walls of which were a number of niches, each one containing a mummy. The place was intolerably close, and was filled with an overpowering odour of dried herbs. In the centre, and side by side, were two alabaster slabs, each about seven feet long by three in width. A stone pillar was at the head of each, but for what purpose the blocks were originally intended I have no idea.

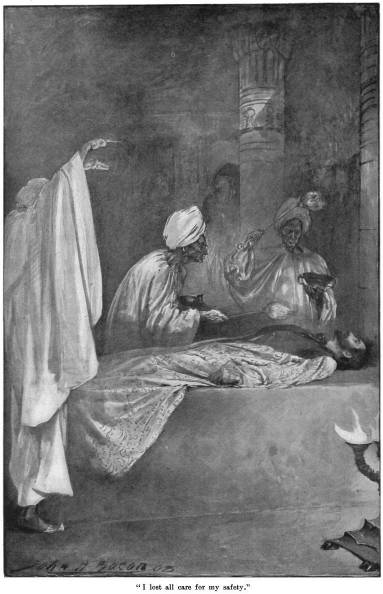

At a signal from my conductor, two beings—I cannot call them men,—who from their faces I should have judged to be as old as Pharos himself, made their appearance, bringing with them certain vestments and a number of curiously shaped bottles. The robes, which were of some white material, were embroidered with hieroglyphics. These they placed about my shoulders, and, when they had done so, the old fellow who had conducted me to the place bade me stretch myself upon one of the slabs I have just mentioned.

Under other circumstances I should have protested most vigorously, but I was in such a. position now that I came to the conclusion that it would not only be useless but most impolitic on my part to put myself in opposition against him thus early in the day. I accordingly did as I was ordered. The two attendants, who were small, thin, and wizened almost beyond belief, immediately began to anoint my face and hands with some sweet-smelling essences taken from the bottles they had brought with them. The perfume of these unguents was indescribably soothing, and gradually I found myself losing the feeling of excitement and distrust which had hitherto possessed me. The cigarettes Pharos had given me on the occasion that I had dined with him in Naples must have contained something of a like nature, for the effect was similar in more than one essential. I refer in particular to the sharpening of the wits, to the feeling of peculiar physical enjoyment, and to the dulling of every sense of fear.

It was just as well, perhaps, that I was in this frame of mind; for though I did not know it, I was about to be put to a test that surpassed in severity anything of which I could have dreamed.

Little by little a feeling of extreme lassitude was overtaking me; I lost all care for my safety, and my only desire was to be allowed to continue in the state of exquisite semi-consciousness to which I had now been reduced. The figures of the men who continued to sprinkle the essences upon me, and of the old man who stood at my feet, his arms stretched above his head as if he were invoking the blessing of the gods upon the sacrifice he was offering to them, faded farther and farther into the rose-coloured mist before my eyes. How long an interval elapsed before I heard the old man's voice addressing me again, I cannot say. It may have been a few seconds, it may have been hours; I only know that, as soon as I heard it, I opened my eyes and looked about me. The attendants had departed, and we were alone together. He was still standing before me, gazing intently down at my face.

"Rise, son of an alien race," he said, "rise purified for the time of thy earthly self, and fit to enter and stand in the presence of Ammon-Ra!"

In response to his command, I rose from the stone upon which I had been lying. Strangely enough, however, I did so without perceptible exertion. In my new-state my body was as light as air, my brain without a cloud, while the senses of hearing, of sight, of smell, and of touch were each abnormally acute.

Taking me by the hand, the old man led me from the room in which the ceremony of anointing had taken place along another passage, on either side of which, as in the apartment we had just left, were a number of shelves, each containing a mummy case. Reaching the end of this passage, he paused and extinguished the torch he carried, and then, still leading me by the hand, entered another hall which was in total darkness. In my new state, however, I experienced no sort of fear, nor was I conscious of feeling any alarm as to my ultimate safety.

Having brought me to the place for which he was making, he dropped my hand, and, from the shuffling of his feet upon the stone pavement, I knew that he was moving away from me.

Having brought me to the place for which he was making, he dropped my hand, and, from the shuffling of his feet upon the stone pavement, I knew that he was moving away from me.

"Wait here and watch," he said, and his voice echoed and re-echoed in that gloomy place. "For it was ordained from the first that this night thou shouldst see the mysteries of the gods. Fear not, thou art in the hands of the watcher of the world, the ever-mighty Harmachis, who sleepeth not day or night, nor hath rested since time began."

With this he departed, and I remained standing where he had put me, watching and waiting for what should follow. To attempt to make you understand the silence that prevailed would be a waste of time, nor can I tell you how long it lasted. Under the influence of the mysterious preparation to which I had been subjected, such things as time, fear, and curiosity had been eliminated from my being.

Suddenly, in the far distance, so small as to make it uncertain whether it was only my fancy or not, a pinpoint of light attracted my attention. It moved slowly to and fro with the regular and evenly-balanced swing of a pendulum, and as it did so it grew larger and more brilliant. Such, was the fascination it possessed for me that I could not take my eyes off it, and as I watched it everything grew bright as noonday. How I had been moved, I know not, but to my amazement I discovered that I was no longer in that subterranean room below the temple, but was in the open air in broad daylight, and standing on the same spot before the main pylon where Pharos and I had waited while the man who had conducted us to the temple went off to give notice of our arrival. There was, however, this difference: the temple which I had seen then was nothing more than a mass of ruins, now it was restored to its pristine grandeur, and exceeded in beauty anything I could have imagined. High into the cloudless sky above me rose the mighty pylons, the walls of which were no longer bare and weather-worn, but adorned with brilliant coloured paintings. Before me—not covered with sand as at present, but carefully tended and arranged with a view to enhancing the already superb effect—was a broad and well-planned terrace from which led a road lined on either side with the same stately krio-sphinxes that today lie headless and neglected on the sands. From the crowds that congregated round these mighty edifices, and from the excitement which prevailed on every hand, it was plain that some great festival was about to be celebrated. While I watched, the commencement of the procession made its appearance on the farther side of the river, where state barges ornamented with much gold and many brilliant colours were waiting to carry it across. On reaching the steps it continued its march towards the temple. It was preceded by a hundred dancing girls clad in white, and carrying timbrels in their hands. Behind them was a priest bearing the two books of Hermes, one containing hymns in honour of the Gods, and the other precepts relating to the life of the King. Next came the Royal Astrologer bearing the measure of Time, the hour-glass and the Phoenix. Then the King's Scribe, carrying the materials of his craft. Following him were more women playing on single and double pipes, harps, and flutes, and after the musicians the Stolistes, with the sign of Justice and the cup of Libation. Next walked twelve servants of the temple, headed by the Chief Priest, clad in his robes of leopard skins, after whom marched a troop of soldiers with the sun glittering on their armour and accoutrements. Behind, the runners were carrying white staves in their hand, and after them fifty singing girls, strewing flowers of all colours upon the path. Then, escorted by his bodyguard, the Royal Arms bearers, and seated upon his throne of state, which again was borne upon the shoulders of the chief eight nobles of the land, and had above it a magnificent canopy, was Pharaoh himself, dressed in his robes of state and carrying his sceptre and the flagellum of Osiris in either hand. Behind him were his fan-bearers, and by his side a man whom, in spite of his rich dress, I recognised as soon as my eyes fell upon him. He was none other than the servant whom Pharaoh delighted to honour, his favourite, Ptahmes, son of Netruhôtep, Chief of the Magicians, and Lord of the North and South. Deformed as he was, he walked with a proud step, carrying himself like one who knows that his position is assured. Following Pharaoh were his favourite generals, then another detachment of soldiers, still more priests, musicians, and dancing girls, and last of all a choir robed in white, and numbering several hundred voices.

Reaching the main pylon of the temple, the dancing girls, musicians and soldiers drew back on either side, and Pharaoh, still borne upon the shoulders of his courtiers, and accompanied by his favourite magician, entered the sacred building and was lost to view.

He had no sooner disappeared than the whole scene vanished, and once more I found myself standing in the darkness. It was only for a few moments, however. Then the globule of light which had first attracted my attention reappeared. Again it swung before my eyes, and again I suddenly found myself in the open air. Now, however, it was night time. As on the previous occasion, I stood before the main pylon of the temple. This time, however, there was no crowd, no brilliant procession, no joyous music. Heavy clouds covered the sky, and at intervals the sound of sullen thunder came across the sands from the west. A cold wind sighed round the corners of the temple and added to the prevailing dreariness. It was close upon midnight, and I could not help feeling that something terrible was about to happen. Nor was I disappointed. Even as I waited, a small procession crossed the Nile and made its way, just as the other had done, up the avenue of krio-sphinxes. Unlike the first, however, this consisted of but four men, or, to be exact, of five, since one was being carried on a bier. Making no more noise than was necessary, they conveyed their burden up the same well-kept roadway and approached the temple. From where I stood I was able to catch a glimpse of the dead man, for dead he certainly was. To my surprise he was none other than Ptahmes. Not, however, the Ptahmes of the last vision. Now he was old and poorly clad, and a very different creature from the man who had walked so confidently beside Pharaoh's litter on the occasion of the last procession.

Knowing as I did the history of his downfall, I was easily able to put two and two together and to ascribe a reason for what I saw. He had been in hiding to escape the wrath of Pharaoh, and now he was dead, and his friends among the priests of Ammon were bringing him by stealth to the temple to prepare his body for the tomb. Once more the scene vanished and I stood in darkness. Then, as before, the light reappeared, and with it still another picture.

On this occasion also it was night, and we were in the desert. The same small party I had seen carrying the dead man before was now making its way towards a range of hills. High up on a rocky spur a tomb had been prepared, and to it the body of the man, once so powerful and now fallen so low, was being conveyed. Unseen by the bearers, I followed, and entered the chamber of death. In front was the Chief Priest, a venerable man, but to my surprise without his leopard-skin dress. The mummy was placed in position without ceremony of any kind. Even the most simple funerary-rites were omitted. No sorrowing relatives made an oblation before it, no scroll of his life was read. Cut off from the world, buried by stealth, he was left to take the long rest in an unhallowed tomb from which my own father, three thousand years later, was destined to remove his body. Then, like the others, this scene also vanished, and once more I found myself standing in the dark hall.

"Thou hast seen the splendour and the degradation of the man Ptahmes," said the deep voice of the old man who had warned me not to be afraid. "How he rose and how he fell. Thou hast seen how the mortal body of him who was once so mighty that he stood before Pharaoh unafraid, was buried by night, having been forbidden to cross the sacred Lake of the Dead. For more than three thousand years, by thy calculation, that body has rested in an unconsecrated tomb, it has been carried to a far country, and throughout that time his soul has known no peace. But the gods are not vengeful for ever, and it is decreed that by thy hand, inasmuch as thou art not of his country or of his blood, he shall find rest at last. Follow me, for there is much for thee to see."

Leading the way across the large hall, he conducted me down another flight of steps into yet another hall—larger than any I had yet seen, the walls of which were covered with frescoes, in every case having some connection with the services rendered to the dead. On a stone slab in the centre of this great place was the mummy case which had for so many years stood in the alcove of my studio, and which was undoubtedly the cause of my being where I now was. I looked again, and could scarcely believe my eyes, for there, seated at its head, gazing from the old man to myself, was the monkey, Pehtes, with an expression of terror upon his wizened little face.

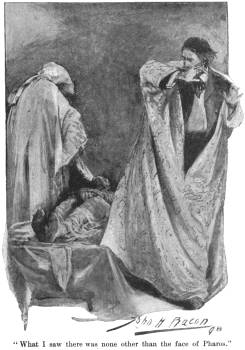

At a signal from my companion, the men who had anointed me on my arrival in this ghostly place made their appearance, but whence I could not discover. Lifting the lid of the case, despite the monkey's almost human protests, they withdrew the body, swaddled up as it was, and laid it upon the table. One by one the cloths were removed until the naked flesh (if flesh it could be called) lay exposed to view. To the best of my belief it had never seen the light, certainly not in my time, since the day, so many thousand years before, when it had been prepared for the tomb. The effect it had upon me was almost overwhelming. My guide, however, permitted no sign of emotion to escape him. When everything had been removed, the men who had done the work withdrew as silently as they had come, and we three were left alone together.

"Draw near," said the old man solemnly, "and if thou wouldst lose conceit in thy strength, and learn how feeble a thing is man, gaze upon the form of him who lies before you. Here on this stone is all that is left of Ptahmes, the son of Netruhôtep, Magician to Pharaoh, and chief of the Prophets of the North and South."

I drew near and looked upon the mummified remains. Dried up and brown as they were, the face was still distinctly recognisable, and as I gazed I sprang back with a cry of horror and astonishment. Believe it or not as you please, but what I saw there was none other than the face of Pharos. The likeness was unmistakable. There could be no sort of doubt about it. I brushed my hand across my eyes to find out if I were dreaming. But no, when I looked again the body was still there. And yet it seemed so utterly impossible, so unheard of, that the man stretched out before me could be he whom I had first seen at the foot of Cleopatra's Needle, at the Academy, in Lady Medenham's drawing-room, and with whom I had dined at Naples after our interview at Pompeii. And as I looked, as if any further proof were wanting, the monkey, with a little cry, sprang upon the dead man and snuggled himself down beside him.

I drew near and looked upon the mummified remains. Dried up and brown as they were, the face was still distinctly recognisable, and as I gazed I sprang back with a cry of horror and astonishment. Believe it or not as you please, but what I saw there was none other than the face of Pharos. The likeness was unmistakable. There could be no sort of doubt about it. I brushed my hand across my eyes to find out if I were dreaming. But no, when I looked again the body was still there. And yet it seemed so utterly impossible, so unheard of, that the man stretched out before me could be he whom I had first seen at the foot of Cleopatra's Needle, at the Academy, in Lady Medenham's drawing-room, and with whom I had dined at Naples after our interview at Pompeii. And as I looked, as if any further proof were wanting, the monkey, with a little cry, sprang upon the dead man and snuggled himself down beside him.

Approaching the foot of the slab, the old man addressed the recumbent figure.

"Open thine eyes, Ptahmes, son of Netruhôtep," he said, "and listen to the words that I shall speak to thee. In the day of thy power, when yet thou didst walk upon the earth, thou didst sin against Ra and against the mighty ones, the thirty-seven gods. Know now that it is given thee for thy salvation to do the work which has been decreed against the peoples upon whom their wrath has fallen. Be strong, O Ptahmes! for the means are given thee, and if thou dost obey thou shalt rest in peace. Wanderer of the centuries, who cometh out of the dusk, and whose birth is from the house of death, thou wast old and art born again. Through all the time that has been thou hast waited for this day. In the name, therefore, of the great gods Osiris and Nephthys, I bid thee rise from thy long rest and go out into the world; but be it ever remembered by thee that if thou usest this power to thy own advantage, or failest even by as much as one single particular in the trust reposed in thee, then thou art lost, not for to-day, not for to-morrow, but for all time. In the tomb from whence it was stolen thy body shall remain until the work which is appointed thee is done. Then shalt thou return and be at peace for ever. Rise, Ptahmes, rise and depart!"

As he said this, the monkey sprang up from the dead man's side with a little cry and beat wildly in the air with his hands. Then it was as if something snapped, my body became deadly cold, and with a great shiver I awoke (if, as I can scarcely believe, I had been sleeping before) to find myself sitting on the same block of stone in the great Hypostile Hall where Pharos had left me many hours before. The first pale light of dawn could be seen through the broken columns to the east. The air was bitterly cold, and my body ached all over as if, which was very likely, I had caught a chill. Only a few paces distant, seated on the ground, their faces hidden in their folded arms, were the two Arabs who had accompanied us from Luxor. I rose to my feet and stamped upon the ground in the hope of imparting a little warmth to my stiffened limbs. Could I have fallen asleep while I waited for Pharos, and if so,, had I dreamed all the strange things that I have described in this chapter? I discarded the notion as impossible, and yet what other explanation had I to offer? I thought of the secret passage beneath the stone, and which led to the vaults below. Remembering as I did the direction in which the old man had proceeded in order to reach it, I determined to search for it. If only I could find the place, I should be able to set all doubt on the subject at rest for good and all. I accordingly crossed the great hall, which was now as light as day, and searched the place which I considered most likely to contain the stone in question. But though I gave it the most minute scrutiny for upwards of a quarter of an hour, no sign could I discover. All the time I was becoming more and more convinced of one thing, and that was the fact that I was unmistakably ill. My head and bones ached, while my left arm, which had never yet lost the small purple mark which I had noticed the morning after my adventure at the Pyramids, seemed to be swelling perceptibly and throbbed from shoulder to wrist. Unable to find the stone, and still more unable to make head or tail of all that had happened in the night, I returned to my former seat. One of the Arabs, the man who had boarded the steamer on our arrival the previous afternoon, rose to his feet and looked about him, yawning heavily as he did so. He, at least, I thought, would be able to tell me if I had slept all night in the same place. I put the question to him, only to receive his solemn assurance that I had not left their side ever since I had entered the ruins. The man's demeanour was so sincere, that I had no reason to suppose that he was not telling the truth. I accordingly seated myself again, and devoutly wished I were back with Valerie on board the steamer.

A nice trick Pharos had played me in bringing me out to spend the night catching cold in these ruins. I resolved to let him know my opinion of his conduct at the earliest opportunity. But if I had gone to sleep on the stone, where had he been all night, and why had he not permitted me to assist in the burial of Ptahmes according to agreement? What was more important still, when did he intend putting in an appearance again? I had half made up mind to set off for Luxor on my own account, in the hope of being able to discover an English doctor, from whom I could obtain some medicine and find out the nature of the ailment from which I was suffering. I was, however, spared the trouble of doing this; for just as my patience was becoming exhausted, a noise behind me made me turn round, and I saw Pharos coming towards me. It struck me that his step was more active than I had yet seen it, and I noticed the pathetic little face of the monkey, Pehtes, peeping out from the shelter of his heavy coat.

"Come," he said briskly, "let us be going. You look cold, my dear Forrester, and if I am not mistaken, you are not feeling very well. Give me your hand."

I did as he ordered me. If, however, my hand was cold, his was like ice.

"I thought as much," he said; "you are suffering from a mild attack of Egyptian fever. Fortunately, however, that can soon be set right"

I followed him through the main pylon to the place where we had dismounted from our camels the night before. The patient beasts were still there just as we had left them.

"Mount," said Pharos, "and let us return with all speed to the steamer."

I did as he desired, and we accordingly set off. I noticed, however, that on the return journey we did not follow the same route as that which had brought us to the temple. By this time, however, I was feeling too ill to protest or to care very much where we went.

"We are nearly there," said Pharos. "Keep up your heart. In less than ten minutes you will be in bed and on the high-road to recovery."

"But this is not the way to Luxor," I said feebly, clinging to the pommel of my saddle as I spoke and looking with aching eyes across the dreary stretch of sand.

"We are not going to Luxor," Pharos replied. "I am taking you to a place where I can look after you myself, and where there will be no chance of any meddlesome European doctors interfering with my course of treatment."

The ten minutes he had predicted seemed like centuries, and, had I been asked, I should have declared that at least two hours elapsed between our leaving the Temple of Ammon and our arrival at our destination. During that time my agony was well-nigh unbearable. My throat was swelling, and I felt as if I were suffocating. My limbs quivered as though they had been stricken with the palsy, and the entire landscape was blotted out by a red mist as thick as blood.

More dead than alive, I accommodated myself to the shuffling tread of the camel as best I could, and when at last I heard Pharos say in Arabic, "It is here; bid the beast lie down," my last ounce of strength departed, and I lost consciousness.

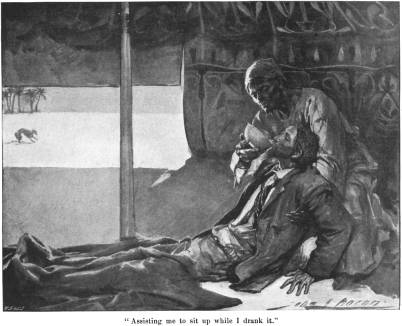

How long I remained in this state, I had no idea at the time; but when I recovered my senses again, I found myself lying in an Arab tent, upon a rough bed made up upon the sand. I was as weak as a kitten, and when I looked at my hand as it lay upon the rough blanket, I scarcely recognised it, so white and emaciated was it. Not being able to understand the reason of my present location, I raised myself on my elbow and looked out under the flap of the tent. All I could see there, however, was desert sand, a half-starved dog prowling about in the foreground in search of something to eat, and a group of palm trees upon the far horizon. While I was thus investigating my surroundings, the same Arab who had assured me that I had slept all night on the block of stone in the temple, made his appearance with a bowl of broth which he gave to me, putting his arm round me and assisting me to sit up while I drank it. I questioned him as to where I was, and how long I had been there; but he only shook his head, saying that he could tell me nothing. The broth, however, did me good, more good than any information could have done, and, after he had left me, I laid myself down and in a few moments was asleep again. When I woke, it was late in the afternoon, and the sun was sinking behind the palm trees to which I referred just now. As it disappeared, Pharos entered the tent and expressed his delight at finding me conscious once more. I put the same questions to him that I had asked the Arab, and found that he was inclined to be somewhat more communicative.

How long I remained in this state, I had no idea at the time; but when I recovered my senses again, I found myself lying in an Arab tent, upon a rough bed made up upon the sand. I was as weak as a kitten, and when I looked at my hand as it lay upon the rough blanket, I scarcely recognised it, so white and emaciated was it. Not being able to understand the reason of my present location, I raised myself on my elbow and looked out under the flap of the tent. All I could see there, however, was desert sand, a half-starved dog prowling about in the foreground in search of something to eat, and a group of palm trees upon the far horizon. While I was thus investigating my surroundings, the same Arab who had assured me that I had slept all night on the block of stone in the temple, made his appearance with a bowl of broth which he gave to me, putting his arm round me and assisting me to sit up while I drank it. I questioned him as to where I was, and how long I had been there; but he only shook his head, saying that he could tell me nothing. The broth, however, did me good, more good than any information could have done, and, after he had left me, I laid myself down and in a few moments was asleep again. When I woke, it was late in the afternoon, and the sun was sinking behind the palm trees to which I referred just now. As it disappeared, Pharos entered the tent and expressed his delight at finding me conscious once more. I put the same questions to him that I had asked the Arab, and found that he was inclined to be somewhat more communicative.

"You have now been ill three days," he said, "so ill, indeed, that I dared not move you. Now, however, that you have got your senses back, you will make rapid progress. I can assure you I shall not be sorry, for events have occurred which necessitate my immediate return to Europe. You on your part, I presume, will not regret saying farewell to Egypt?"

"I would leave to-day, if such a thing were possible," I answered. "Weak as I am, I think I could find strength enough for that. Indeed, I feel stronger already, and, as a proof of it, my appetite is returning. Where is the Arab who brought me my broth this morning?"

"Dead," said Pharos laconically. "He held you in his arms and died two hours afterwards. They've no stamina, these Arabs—the least thing kills them. But you need have no fear. You have passed the critical point, and your recovery is certain."

But I scarcely heard him. "Dead! dead!" I was saying over and over again to myself as if I did not understand it. "Surely the man cannot be dead?" He had died through helping me. What, then, was this terrible disease of which I had been the victim?

CHAPTER XIV.

IN travelling either with Pharos or in search of him, it was necessary to accustom one's self to rapid movement. I was in London on June 7th, and had found him in Naples three days later; had reached Cairo in his company on the 18th of the same month, and was four hundred and fifty miles up the Nile by the 27th. I had explored the mysteries of the great Temple of Ammon as no other Englishman, I feel convinced, had ever done; had been taken seriously ill, recovered, returned to Cairo, travelled thence to rejoin the yacht at Port Said; had crossed in her to Constantinople, journeyed by the Orient Express to Vienna, and on the morning of July 15th stood at the entrance to the Teyn Kirche in the wonderful old Bohemian city of Prague.

From this itinerary it will be seen that the grass was not allowed to grow under our feet. Indeed, we had scarcely arrived in any one place before our remorseless leader hurried us away again. His anxiety to return to Europe was as great as it had been to reach Egypt. On land the trains could not travel fast enough; on board the yacht his one cry was, "Push on, push on!" What this meant to a man like myself, who had lately come so perilously near death, I must leave you to imagine. Indeed, looking back upon it now, I wonder that I emerged from it alive.

We had reached Constantinople early on Thursday morning, and had left for Vienna at four o'clock in the afternoon. In the latter place we had remained only a few hours, had caught the next available train, and reached Prague the following morning. What our next move would be I had not the least idea, nor did Pharos enlighten me upon the subject. Times out of number I made up my mind that I would speak to him about it, and let him see that I was tired of so much travelling, and desired to return to England forthwith. But I could not leave Valerie, and whenever I began to broach the subject my courage deserted me, and it did not require much self-persuasion to make me put the matter off for a more convenient opportunity,

Of the Fräulein Valerie, up to the time of our arrival in the city, there is little to tell. She had evidently been informed of my illness at Karnak, for when I returned to the steamer she had arranged that everything should be in readiness for my reception. By the time we reached Cairo again I was so far recovered as to be able to join her on deck, but by this time a curious change had come over her: she was more silent and much more reserved than heretofore, and, when we reached the yacht, spent most of her days in her own cabin, where I could hear her playing to herself such wild, sad music that to listen to it made me feel miserable for hours afterwards. With Pharos, however, it was entirely different. He, who had once been so morose, now was all smiles; while his inseparable companion, the monkey, Pehtes, for whom I had conceived a dislike that was only second to that I entertained for his master, equalled, if he did not excel him, in the boisterousness of his humour.

At the commencement of this chapter I have said that on this particular morning, our first in Prague, I was standing before the doors of the Teyn Kirche, beneath the story of the Crucifixion as it is told there in stone. My reason for being there will be apparent directly. Let it suffice that, when I entered the sacred building, I paused, thinking how beautiful it was, with the sunshine straggling in through those wonderful windows. With the exception, however, of myself and a kneeling figure near the entrance to the Marian Capelle, no worshippers were in the church. Though I could not see her face, I knew that it was Valerie. Her head was bent upon her hands and her shoulders shook with emotion. She must have heard my step upon the stones, for she suddenly looked up, and, seeing me before her, rose from her knees and prepared to leave the pew. The sight of her unhappiness affected me keenly, and when she reached the spot where I was standing, I could control myself no longer. For the last few weeks I had been hard put to it to keep my love within bounds, and now, under the influence of her grief, it got the better of me altogether. She must have known what was coming, for she stood before me with a troubled expression in her eyes.

"Mr. Forrester," she began, "I did not expect to see you. How did you know that I was here?"

"Because I followed you," I answered unblushingly.

"You followed me?" she said.

"Yes, and I am not ashamed to own it," I replied. "Surely you can understand why?"

"I am afraid I do not," she answered, and, as she did so, she took a step away from me, as if she were afraid of what she was going to hear.

"In that case there is nothing left but for me to tell you," I said, and, approaching her, I took possession of the slender hand which rested upon the back of the pew behind her. "I followed you, Valerie, because I love you, and because I wished to guard you. Unhappily, we have both of us the best of reasons for knowing that we are in the power of a man who would stop at nothing to achieve any end he might have in view. Did you hear me say, Valerie, that I love you?"

From her beautiful face every speck of colour had vanished by this time; her bosom heaved tumultuously under the intensity of her emotion. No word, however, passed her lips. I still held her hand in mine, and it gave me courage to continue when I saw that she did not attempt to withdraw it.

"Have you no answer for me?" I inquired, after the long pause which had followed my last speech. "I have told you that I love you. If it is not enough, I will do so again. What better place could be found for such a confession than this beautiful old church, which has seen so many lovers and has held the secrets of so many lives? Valerie, I believe I have loved you since the afternoon I first saw you. But since I have known you and have learnt your goodness, that love has become doubly strong."

"I cannot hear you!" she cried, almost with a sob; "indeed, I cannot. You do not know what you are saying. You have no idea of the pain you are causing me."

"God knows I would not give you pain for anything," I answered. "But now you must hear me. Why should you not? You are a good woman, and I am, I trust, an honest man. Why, therefore, should I not love you? Tell me that."

"Because it is madness," she answered in despair. "Situated as we are, we should be the last to think of such a thing. Oh, Mr. Forrester, if only you had taken my advice, and had gone away from Naples when I implored you to do so, this would not have happened."

"If I have anything to be thankful for, it is that," I replied fervently. "I told you then that I would not leave you. Nor shall I ever do so until I know that your life is safe. Come, Valerie, you have heard my confession— will you not be equally candid with me? You have always proved yourself my friend. Is it possible you have nothing more than friendship to offer me?"

I knew the woman I was dealing with. Her beautiful, straightforward nature was incapable of dissimulation.

"Mr. Forrester, even if what you hope is impossible, it would be unfair on my part to deceive you," she said. "I love you, as you are worthy to be loved, but having said that I can say no more. You must go away and endeavour to forget that you ever saw so unhappy a person as myself."

"Never," I answered, and then dropping on one knee and pressing her hand to my lips, I continued: "You have confessed, Valerie, that you love me, and nothing can ever separate us now. Come what may, I will not leave you. Here, in this old church, by the cross on yonder altar, I swear it. As we are together in trouble, so will we be together in love, and may God's blessing rest upon us both."

"Amen," she answered solemnly.

She seated herself in a pew, and I took my place beside her.

"Valerie," I said, "I followed you this morning for two reasons. The first was to tell you of my love, and the second was to let you know that I have made up my mind on a certain course of action. At any risk we must escape from Pharos, and since you have confessed that you love me, we will go together."

"It is useless," she answered sorrowfully, "quite useless."

"Hush!" I said, as three people entered the church. "We cannot talk here. Let us find another place."

With this we rose and left the building. Proceeding into the street, I hailed a cab, and as soon as we had taken our places in it, bade the man drive us to the Baumgarten. When we had found a seat in a secluded spot, we resumed the conversation that had been interrupted in the church.

"You say that it is useless our thinking of making our escape from this man?" I said. "I tell you that it is not useless, and that at any hazard we must do so. We know now that we love each other. I know, at least, how much you are to me. Is it possible, therefore, that you can believe I should allow you to remain in his power an instant longer than I can help? In my life I have not feared many men, but I confess that I fear Pharos as I do the devil. Since I have known him, I have had several opportunities of testing his power. I have seen things, or he has made me believe I have seen things, which, under any other circumstances, would seem incredible, and, if it is likely to have any weight with you, I do not mind owning that his power over me is growing greater every day. And that reminds me there is a question I have often desired to ask you. Do you remember one night on board the yacht, when we were crossing from Naples to Port Said, telling Pharos that you could see a cave in which a mummy had once stood?"

She shook her head.

"I remember nothing of it," she said. "But why do you ask me such strange questions?"

I took her hand before I answered. I could feel that she was trembling violently.

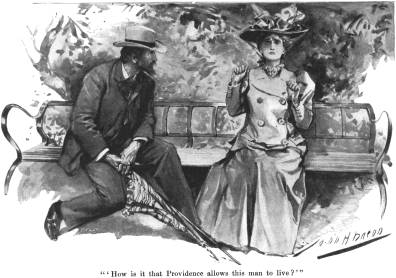

"Because I want to prove to you the diabolical power the man possesses. You described a tomb from which the mummy had been taken. I have seen that tomb. It was the burial-place of the Magician, Ptahmes, whose mummy once stood in my studio in London, which Pharos stole from me, and which was the primary cause of my becoming associated with him. You described a subterranean hall with carved pillars and paintings on the walls, and a mummy lying upon a block of stone. I have seen that hall, those pillars, those carvings and paintings, and the mummy of Ptahmes lying stretched out as you portrayed it. You mentioned a tent in the desert and a sick man lying on a bed inside it I was that sick man, and it was to that tent that Pharos conveyed me after I had spent the night in the ruins of the Temple of Ammon. The last incident has yet to take place; but, please God, if you will help me in my plan, we shall have done with him long before then."

"You say you saw all the things I described. Please do not think me stupid, but I do not understand how you could have done so."

Thereupon I told her all that had befallen me at the ruins of Karnak. She listened with feverish interest.

"How is it that Providence allows this man to live?" she cried when I had finished. "Who is he and what is the terrible power he possesses? And what is to be the end of all his evil ways?"

"How is it that Providence allows this man to live?" she cried when I had finished. "Who is he and what is the terrible power he possesses? And what is to be the end of all his evil ways?"

"That is a problem which only the future can solve," I answered. "For ourselves it is sufficient that we must get away from him and at once. Nothing could be easier. He exercises no control over our movements. He does not attempt to detain us. We go in and out as we please, therefore all we have to do is to get into a train and be hundreds of miles away before he is even aware that we are outside the doors of the hotel. You are not afraid, Valerie, to trust yourself and your happiness to me?"

"I would trust myself with you anywhere," she answered; and as she said it she pressed my hand and looked into my face with her brave, sweet eyes. "And for your sake I would do and bear anything."

Brave as her words were, however, a little sigh escaped her lips before she could prevent it.

"Why do you sigh?" I asked. "Have you any doubt as to the safety of our plan? If so, tell me, and I will change it."

"I have no doubt as to the plan," she answered. "All I fear is that it may be useless. I have already told you how I have twice tried to escape him, and how on each occasion he has brought me back."

"He shall not do so this time," I said with determination. "We will lay our plans with the greatest care, behave towards him as if we contemplated remaining for ever in his company, and then to-morrow morning we will catch the train for Berlin, be in Hamburg next day, and in London three days later. Once there, I have a hundred friends who, when I tell them that you are hiding from a man who has treated you most cruelly, and that you are about to become my wife, will be only too proud to take you in. Then we will be married as quickly as can be arranged, and as man and wife defy Pharos to do his worst."

She did her best to appear delighted with my plan, but I could see that she had no real faith in it. Nor, if the truth must be told, was I in my own heart any too sanguine of success. I could not but remember the threat the man had held over me that night in the Pyramid at Gizeh: "For the future you are my property, to do with as I please. You will have no will but my pleasure, no thought but to act as I shall tell you." However, we could but do our best, and I was determined it should not be my fault if our enterprise did not meet with success. Not once but a hundred times we overhauled our plan, tried its weak spots, arranged our behaviour before Pharos, and endeavoured to convince each other as far as possible that it could not fail. And if we did manage to outwit him, how proud I should be to parade this glorious creature in London as my wife! and as I thought of the happiness the future might have in store for us, and remembered that it all depended on that diabolical individual Pharos, I felt sick and giddy with anxiety to see the last of him.

Not being anxious to arouse any suspicion in our ogre's mind by a prolonged absence, we at last agreed that it was time for us to think of returning. Accordingly, we left the park and, finding the cab which had been ordered to wait for us at the gates, drove back to the city. On reaching the hotel, we discovered Pharos in the hall, holding in his hand a letter which he had just finished reading as we entered. On seeing us, his wrinkled old face lit up with a smile.

"My dear," he said to Valerie, placing his hand upon her arm in an affectionate manner, "a very great honour has been paid you. His Majesty, the Emperor King, as you are perhaps aware, arrived in the city yesterday, and to-night a state concert is to be given at the palace. Invitations have been sent to us, and I have been approached in order to discover whether you will consent to play. Not being able to find you, I answered that I felt sure you would accept his Majesty's command. Was I right in so doing?"

Doubtless, remembering the contract we had entered into together that morning to humour Pharos as far as possible, Valerie willingly gave her consent. Though did not let him see it, I for my part was not so pleased. He should have waited and have allowed her to accept or decline for herself, I thought. However, I held my peace, trusting that on the morrow we should be able to make our escape and so be done with him for good and all.

For the remainder of the day Pharos exhibited the most complete good-humour. He was plainly looking forward to the evening. He had met Franz Josef on more than one occasion, he informed me, and remembered with gusto the compliments that had been paid him the last time about his ward's playing.

"I am sure we shall both rejoice in her success, shall we not, my dear Forrester?" he said; and as he did so he glanced slyly at me out of the corner of his eye. "As you can see for yourself, I have discovered your secret."

I looked nervously at him. What did he mean by this? Was it possible that by that same adroit reasoning he had discovered our plan for escaping on the following day?

"I am afraid I do not quite understand," I replied, with as much nonchalance as I could manage to throw into my voice. "Pray, what secret have you discovered?"

"That you love my ward," he answered. "But why look so concerned? It does not require very great perceptive powers to see that her beauty has exercised considerable effect upon you. Why should it not have done so? And where would be the harm? She is a most fascinating woman, and you, if you will permit me to tell you so to your face, are—what shall we say?—well, far from being an unprepossessing man. Like a foolish guardian, I have permitted you to be a good deal, perhaps too much, together, and the result even a child might have foreseen. You have learnt to love each other. No; do not be offended. I assure you there is no reason for it. I like you, and I promise you, if you continue to please me, I shall raise no objection. Now what have you to say to me?"

"I do not know what to say," I said, and it was the truth. "I had no idea you suspected anything of the kind."

"I fear you do not give me the credit of being very sharp," he replied. "And perhaps it is not to be wondered at. An old man's wits cannot hope to be as quick as those of the young. But there, we have talked enough on this subject; let us postpone consideration of it until another day."

"With all my heart," I answered. "But there is one question I had better ask you while I have the opportunity. I should be glad if you could tell me how long you are thinking of remaining in Prague. When I left England, I had no intention of being away from London more than a fortnight, and I have now trespassed on your hospitality for upwards of two months. If you are going west within the next week or so, and will let me travel with you, I shall be only too glad to do so, otherwise I fear I shall be compelled to bid you good-bye and return to England alone."

"You must not think of such a thing," he answered, this time throwing a sharp glance at me from his sunken eyes. "Neither Valerie nor I could get on without you. Besides, there is no need for you to worry. Now that this rumour is afloat, I have no intention of remaining here any longer than I can help."

"To what rumour do you refer?" I inquired. "I have heard nothing."

"That is what it is to be in love," he replied. "You have not heard, then, that one of the most disastrous and terrible plagues of the last five hundred years has broken out on the shores of the Bosphorus, and is spreading with alarming rapidity through Turkey and the Balkan States."

"I have not heard a word about it," I said, and as I did so I was conscious of a vague feeling of terror in my heart, that fear for a woman's safety which comes some time or another to every man who loves. "Is it only newspaper talk, or is it really as serious as your words imply?"

"It is very serious," he answered. "See, here is a man with the evening paper. I will purchase one and read you the latest news."

He did so, and searched the columns for what he wanted. Though I was able to speak German, I was unable to read it; Pharos accordingly translated for me.

"The outbreak of the plague which has caused so much alarm in Turkey," he read, "is, we regret having to inform our readers, increasing instead of diminishing, and to-day fresh cases to the number of seven hundred and thirty-three have been notified. For the twenty-four hours ending at noon the death-rate has equalled 80 per cent, of those attacked. The malady has now penetrated into Russia, and three deaths were registered as resulting from it in Moscow, two in Odessa, and one in Kiev yesterday. The medical experts are still unable to assign a definite name to it, but incline to the belief that it is of Asiatic origin, and will disappear with the break up of the present phenomenally hot weather."

"I do not like the look of it at all," he said, when he had finished reading. "I have seen several of these outbreaks in my time, and I shall be very careful to keep well out of this one's reach."

"I agree with you," I answered, and then bade him good-bye and went upstairs to my room, more than ever convinced that it behoved me to get the woman I loved out of the place without loss of time.

The concert at the palace that night was a brilliant success in every way, and never in her career had Valerie looked more beautiful or played so exquisitely as on that occasion. Of the many handsome women present that evening she was undoubtedly the queen. And when, after her performance, she was led up and presented to the Emperor by Count de Schelyani, an old friend of her father's, a murmur of such admiration ran through the room as those walls had seldom heard before. I, also, had the honour of being presented by the same nobleman, whereupon his Majesty was kind enough to express his appreciation of my work. It was not until a late hour that we reached our hotel again. When we did, Pharos, whom the admiration Valerie had excited seemed to have placed in a thoroughly good humour, congratulated us both upon our success, and then, to my delight, bade us good-night and took himself off to his bed. As soon as I heard the door of his room close behind him, and not until then, I took Valerie's hand.

"I have made all the arrangements for our escape tomorrow," I whispered, "or rather I should say to-day, since it is after midnight. The train for Berlin, via Dresden, I have discovered, leaves here at a quarter past six. Do you think you can manage to be ready so early?"

"Of course I can," she answered confidently. "You have only to tell me what you want, and I will do it."

"I have come to the conclusion," I said, "that it will not do for us to leave by the city station. Accordingly, I have arranged that a cab shall be waiting for us in the Platz. We will enter it and drive down the line, board the train, and bid farewell to Pharos for good and all."

Ten minutes later I had said good-night to her and had retired to my room. The clocks of the city were striking two as I entered it. In four hours we should be leaving the house to catch the train which we hoped would bring us freedom. Were we destined to succeed or not?

CHAPTER XV.

SO anxious was I not to run any risk of being asleep at the time we had arranged to make our escape that I did not go to bed at all, but seated myself in an armchair and endeavoured to interest myself in a book until the fateful hour arrived. Then, leaving a note upon my dressing-table, in which was contained a sufficient sum to reimburse the landlord for my stay with him, I slipped into one pocket the few articles I had resolved to carry with me, and taking care that my money was safely stowed away in another, I said goodbye to my room and went softly down the stairs to the large hall. Fortune favoured me, for only one servant was at work there, an elderly man with a stolid, good-humoured countenance, who glanced up at me, and being satisfied as to my respectability, continued his work once more. Of Valerie I could see no sign, and since I did not know where her room was situated, I occupied myself, while I waited, wondering what I should do if she had overslept herself and did not put in an appearance until too late. In order to excuse my presence downstairs at such an early hour, I asked the man in which direction the cathedral lay, and whether he could inform me at what time early mass was celebrated.

He had scarcely instructed me on the former point, and declared his ignorance of the latter, before Valerie appeared at the head of the stairs and descended to meet me, carrying her violin case in her hand. I greeted her in English, and after I had slipped a couple of florins into the servant's hand, we left the hotel together and made our way in the direction of the Platz, where to my delight I found the cab I had ordered the previous afternoon already waiting for us. We took our places, and I gave the driver his instructions. In less than a quarter of an hour he had brought us to the station I wanted to reach. I had taken the tickets, and the train was carrying us away from Prague and the man whom we devoutly hoped we should never see again as long as we lived. Throughout the drive we had scarcely spoken a couple of dozen words to each other, having been far too much occupied with the affairs of the moment to think of anything but our flight. Knowing Pharos as we did, it seemed more than probable that he might even now be aware of our escape, and be taking measures to ensure our return. But when we found ourselves safely in the train, our anxiety lessened somewhat, and with every mile we threw behind us our spirits returned. By the time we reached Dresden we were as happy a couple as any in Europe, and when some hours later we stepped out of the carriage on to the platform at Berlin, we were as unlike the pair who had left the hotel at Prague as the proverbial chalk is like cheese. Even then, however, we were determined to run no risk. Every mile that separated us from Pharos meant greater security, and it was for this reason I had made up my mind to reach the German capital, if possible, instead of remaining at Dresden, as had been our original intention.

When our train reached its destination, it was a few minutes after six o'clock, and for the first time in my life I stood in the capital of the German empire. Though we had been travelling for more than ten hours, Valerie had so far shown no sign of fatigue.

"What do you propose doing now?" she inquired, as we stood together on the platform.

"Obtain some dinner," I answered, with a promptness and directness worthy of the famous Mr. Dick.

"You must leave that to me," she said, with one of her own bright smiles, which had been so rare of late. "Remember I am an old traveller, and probably know Europe as well as you know Piccadilly."

"I will leave it to you, then," I answered, "and surely man had never a fairer pilot."

"On any other occasion I should warn you to beware of compliments," she replied, patting me gaily on the arm with her hand, "but I feel so happy now that I am compelled to excuse you. To-night, for the last time, I am going to play the part of your hostess. After that it will be your duty to entertain me. Let us leave by this door."

So saying, she led me from the station into the street outside, along which we passed for some considerable distance. Eventually we reached a restaurant, before which Valerie paused.

"The proprietor is an old friend of mine," she said, "who, though he is acquainted with Pharos, will not, I am quite sure, tell him he has seen us,"

We entered, and when the majordomo came forward to conduct us to a table, Valerie inquired whether his master were visible. The man stated that he would find out, and departed on his errand.

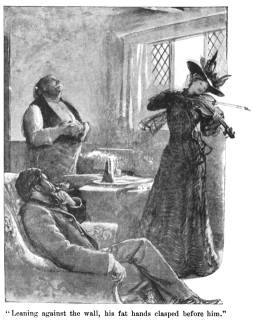

While we waited I could not help noticing the admiring glances that were thrown at my companion by the patrons of the restaurant, among whom were several officers in uniform. Just, however, as I was thinking that some of the latter would be none the worse for a little lesson in manners, the shuffling of feet was heard, and presently, from a doorway on the right, the fattest man I have ever seen in my life made his appearance. He wore carpet slippers on his feet, and a red cap upon his head, and carried in his hand a long German pipe with a china bowl. His face was clean shaven, and a succession of chins fell one below another, so that not an inch of his neck was visible. Having entered the room, he paused, and when the waiter had pointed us out to him as the lady and gentleman who had asked to see him, he approached and affected a contortion of his anatomy which was evidently intended to be a bow.

"I am afraid, Herr Schuncke, that you do not remember me," said Valerie, after the short pause which followed.

The man looked at her rather more closely, and a moment later was bowing even more profusely and inelegantly than before.

"My dear young lady," he said, "I beg your pardon ten thousand times. For the moment, I confess, I did not recognise you. Had I done so, I should not have kept you standing here so long."

Then, looking round, with rather a frightened air, he added, "But I do not see Monsieur Pharos? Perhaps he is with you, and will be here presently?"

"I sincerely hope not," Valerie replied. "That is the main reason of my coming to you." Then, sinking her voice to a whisper, she added, as she saw the man's puzzled expression, "I know I can trust you, Herr Schuncke. The truth is, I have run away from him."

"Herr Gott!" said the old fellow. "So you have run away from him. Well, I do not wonder at it, but you must not tell him I said so. How you could have put up with him so long, I do not know; but that is no business of mine. But I am an old fool; while I am talking so much, I should be finding out how I can be of assistance to you."

"You will not find that very difficult," she replied. "All we are going to trouble you for is some dinner, and your promise to say nothing, should Monsieur Pharos come here in search of us."

"I will do both with the utmost pleasure," he answered. "You may be sure I will say nothing, and you shall have the very best dinner old Ludwig can cook. What is more, you shall have it in my own private sitting-room, where you will be undisturbed. Oh, I can assure you, Fräulein, it is very good to see your face again."

"It is very kind of you to say so," said Valerie, "and also to take so much trouble. I thank you."

"You must not thank me at all," the old fellow replied. "But some day, perhaps, you will let me hear you play again." Then, pointing to the violin-case, which I carried in my hand, he continued, "I see you have brought the beautiful instrument with you. Ah, Gott! what recollections it conjures up for me. I can see old—but there, there, come with me, or I shall be talking half the night!"

We accordingly followed him through the door by which he had entered, and along a short passage to a room at the rear of the building. Here he bade us make ourselves at home, while he departed to see about the dinner. Before he did so, however, Valerie stopped him.

"Herr Schuncke," she said, "before you leave us, I want your congratulations. Let me introduce you to Mr. Forrester, the gentleman to whom I am about to be married."

The old fellow turned to me, and gave another of his grotesque bows.

"Sir," he said, "I congratulate you with all my heart. To hear her play always, ah! what good fortune for a man! You will have a treasure in your house that no money could buy. Be sure that you treat her as such."

When I had promised to do so, the warm-hearted old fellow departed on his errand.

"I hope all this travelling has not tired you, dearest?" I said, when the waiter had handed us our coffee, and had left the room.

"You forget that I am an old traveller," she said, "and not likely to be fatigued by such a short journey. You have some reason, however, for asking the question. What is it?"

"I will tell you," I answered. "I have been thinking that it would not be altogether safe for us to remain in Berlin. It is quite certain that, as soon as he discovers that we are gone, Pharos will make inquiries, and find out what trains left Prague in the early morning. He will then put two and two together, after his own diabolical fashion, and as likely as not, he will be here in search of us to-morrow morning, if not sooner."

"In that case, what do you propose doing?" she asked.

"I propose, if you are not too tired, to leave here by the express at half-past seven," I replied, "and travel as far as Wittenberge, which place we should reach by half-past ten. We can manage it very easily. I will telegraph for rooms, and to-morrow morning early we can continue our journey to Hamburg, where we shall have no difficulty in obtaining a steamer for London. Pharos would never think of looking for us in a small place like Wittenberge, and we should be on board the steamer and en route to England by this time to-morrow evening."

"I can be ready as soon as you like," she answered bravely, "but before we start you must give me time to reward Herr Schuncke for his kindness to us."

A few moments later, our host entered the room. I was about to pay for our meal, when Valerie stopped me.

"You must do nothing of the kind," she said; "remember, you are my guest. Surely you would not deprive me of one of the greatest pleasures I have had for a long time?"

"You shall pay with all my heart," I answered, "but not with Pharos' money."

"I never thought of that," she replied, and her beautiful face flushed crimson. "No, no, you are quite right. I could not entertain you with his money. But what am I to do? I have no other."

"In that case you must permit me to be your banker," I answered, and with that I pulled from my pocket a handful of German coins.

Herr Schuncke at first refused to take anything, but when Valerie declared that if he did not do so she would not play to him, he reluctantly consented, vowing at the same time that he would not accept it himself, but would bestow it upon Ludwig. Then Valerie went to the violin-case, which I had placed upon a side table, and taking her precious instrument from it —the only legacy she had received from her father—tuned it, and stood up to play. As Valerie informed me later, the old man, though one would scarcely have imagined it from his commonplace exterior, was a passionate devotee of the beautiful art, and now he stood, leaning against the wall, his fat hands clasped before him, and his upturned face expressive of the most celestial enjoyment. Nor had Valerie, to my thinking, ever done herself greater justice. She had escaped from a life of misery that had been to her a living death, and her whole being was in consequence radiant with happiness; this was reflected in her playing. Nor was the effect she produced limited to Herr Schuncke. Under the influence of her music, I found myself building castles in the air, and upon such firm foundations, too, that for the moment it seemed no wind would ever be strong enough to blow them down. When she ceased, Schuncke uttered a long sigh, as much as to say, "It will be many years before I shall hear anything like that again," and then it was time to go. The landlord accompanied us into the street and called a cab. Then turning to Schuncke, she held out her hand. "Good-bye," she said, "and thank you for your kindness. I know that you will say nothing about having seen us."

Herr Schuncke at first refused to take anything, but when Valerie declared that if he did not do so she would not play to him, he reluctantly consented, vowing at the same time that he would not accept it himself, but would bestow it upon Ludwig. Then Valerie went to the violin-case, which I had placed upon a side table, and taking her precious instrument from it —the only legacy she had received from her father—tuned it, and stood up to play. As Valerie informed me later, the old man, though one would scarcely have imagined it from his commonplace exterior, was a passionate devotee of the beautiful art, and now he stood, leaning against the wall, his fat hands clasped before him, and his upturned face expressive of the most celestial enjoyment. Nor had Valerie, to my thinking, ever done herself greater justice. She had escaped from a life of misery that had been to her a living death, and her whole being was in consequence radiant with happiness; this was reflected in her playing. Nor was the effect she produced limited to Herr Schuncke. Under the influence of her music, I found myself building castles in the air, and upon such firm foundations, too, that for the moment it seemed no wind would ever be strong enough to blow them down. When she ceased, Schuncke uttered a long sigh, as much as to say, "It will be many years before I shall hear anything like that again," and then it was time to go. The landlord accompanied us into the street and called a cab. Then turning to Schuncke, she held out her hand. "Good-bye," she said, "and thank you for your kindness. I know that you will say nothing about having seen us."

"You need have no fear on that score," he said. "Pharos shall hear nothing from me, I can promise you that. Farewell, Fräulein, and may your life be a happy one."

I said good-bye to him, and then took my place in the vehicle beside Valerie. A quarter of an hour later we were on our way to Wittenberge, and Berlin, like Prague, was only a memory. Before leaving the station I had purchased an armful of papers, illustrated and otherwise, for Valerie's amusement. Though she professed to have no desire to read them, but to prefer sitting by my side, holding my hand, and talking of the happy days we hoped and trusted were before us, she found time, as the journey progressed, to skim their contents. Seeing her do this brought the previous evening to my remembrance, and I inquired what further news there was of the terrible pestilence which Pharos had declared to be raging in eastern Europe.

"I am afraid it is growing worse instead of better," she answered, when she had consulted the paper. "The latest telegram declares that there have been upwards of a thousand fresh cases in Turkey alone within the past twenty-four hours, that it has spread along the Black Sea as far as Odessa, and north as far as Kiev. Five cases are reported from Vienna; and, stay, here is a still later telegram in which it says"—she paused, and a look of horror came into her face—" Can this be true?—it says that the pestilence has broken out in Prague, and that the Count de Schelyani, who, you remember, was so kind and attentive to us last night at the palace, was seized this morning, and at the time this telegram was despatched, was lying in a critical condition."

"That is bad news indeed," I said. "Not only for Austria, but also for us."

"How for us?" she asked.

"Because it will make Pharos move out of Prague," I replied. "When he spoke to me yesterday of the way in which this disease was gaining ground in Europe, he seemed visibly frightened, and stated that as soon as it came too near he should at once leave the city. We have had one exhibition of his cowardice, and you may be sure he will be off now, as fast as trains can take him. It must be our business to take care that his direction and ours are not the same."

"But how are we to tell in which direction he will travel?" asked Valerie, whose face had suddenly grown bloodless in its pallor.

"We must take our chance of that," I answered. "My principal hope is that knowing, as he does, the whereabouts of the yacht, he will make for her, board her, and depart for mid-ocean, to wait there until all danger is passed. For my own part, I am willing to own that I do not like the look of things at all. I shall not feel safe until I have got you safely into England, and that little silver streak of sea is between us and the Continent."

"You do love me, Cyril, do you not?" she inquired, slipping her little hand into mine, and looking into my face with those eyes that seemed to grow more beautiful with every day I looked into them. "I could not live without your love now."

"God grant you may never be asked to do so," I answered. "I love you, dearest, as I believe man never loved woman before, and, come what may, nothing shall separate us. Surely even death itself could not be so cruel. But why do you talk in this dismal strain? The miles are slipping behind us; Pharos, let us hope, is banished from our lives for ever; we are together, and as soon as we reach London, we shall be man and wife. No, no, you must not be afraid, Valerie."

"I am afraid of nothing," she answered, "when I am with you. But ever since we left Berlin I seem to have been overtaken by a fit of melancholy which I cannot throw off. I have reasoned with myself in vain. Why I should feel like this, I cannot think. It is only transitory, I am sure; so you must bear with me; to-morrow I shall be quite myself again."

"Bear with you, do you say?" I answered. "You know that I will do so. You have been so brave till now, that I cannot let you give way just at the moment when happiness is within your reach. Try and keep your spirits up, my darling, for both our sakes. To-morrow you will be on the blue sea, with the ship's head pointing for old England. And after that—well, I told you just now what would happen then."

In spite of her promises, however, I found that in the morning my hopes were not destined to be realized. Though she tried hard to make me believe that the gloom had passed, it needed very little discernment upon my part to see that the cheerfulness she affected was all assumed, and, what made it doubly hard to bear, that it was for my sake.

Our stay at Wittenberge was not a long one. As soon as we had finished our breakfast, we caught the 8.30 express and resumed our journey to Hamburg, arriving there a little before midday. Throughout the journey, Valerie had caused me considerable anxiety. Not only had her spirits reached a lower level than they had yet attained, but her face, during the last few hours, had grown singularly pale and drawn; and when I at last drove her to it, she broke down completely, and confessed to feeling far from well.

"But it cannot be anything serious!" she cried. "I am sure it cannot. It only means that I am not such a good traveller as I thought. Remember, we have covered a good many hundred miles in the last week, and we have had more than our share of anxiety. As soon as we reach our hotel in Hamburg, I will go to my room and lie down. After I have had some sleep, I have no doubt I shall be myself again."

I devoutly hoped so; but in spite of her assurance, my anxiety was in no way diminished. Obtaining a cab, we drove at once to the Hotel Continental, at which I had determined to stay. Here I engaged rooms as usual for Mr. and Miss Clifford, for it was as brother and sister we had decided to pass until we should reach England and be made man and wife. It was just luncheon-time when we arrived there; but Valerie was so utterly prostrated that I could not induce her to partake of anything. She preferred, she declared, to retire to her room at once, and believing that this would be the wisest course for her to pursue, I was only too glad that she should do so. Accordingly, when she had left me, I partook of lunch alone, but with no zest, as may be supposed, and having despatched it, put on my hat and made my way to the premises of the Steamboat Company in order to inquire about a boat for England.

On arrival at the office in question, it was easily seen that something unusual had occurred. In place of the business-like hurry to which I was accustomed, I found the clerks lolling listlessly at their desks. So far as I could see, they had no business wherewith to occupy themselves. Approaching the counter, I inquired when their next packet would sail for the United Kingdom, and in return received a staggering reply.

"I am afraid, sir," said the man, "you will find considerable difficulty in getting into England just now."

"Difficulty in getting into England?" I cried in astonishment; "and why so, pray?"

"Surely you must have heard?" he replied, and looking me up and down as if I were a stranger but lately arrived from the moon. The other clerks smiled incredulously.

"I have heard nothing," I replied, a little nettled at the fellow's behaviour. "Pray be kind enough to inform me what you mean. I am most desirous of reaching London at once, and will thank you to be good enough to tell me when, and at what hour, your next boat leaves?"

"We have no boat leaving," the clerk answered, this time rather more respectfully than before. "Surely, sir, you must have heard that there have been two cases of the plague notified in this city to-day, and more than a hundred in Berlin; consequently, the British Government have closed their ports to German vessels, and, as it is rumoured that the disease has made its appearance in France, it is doubtful whether you will get into a French port either."

"But I must reach England," I answered desperately. "My business is most important. I do not know what I shall do if I am prevented. I must sail to-day, or to-morrow at latest."

"In that case, sir, I am afraid it is out of my power to help you," said the man. "We have received a cablegram from our London office this morning advising us to despatch no more boats until we receive further orders."

"Are you sure there is no other way in which you can help me?" I asked. "I shall be glad to pay anything in reason for the accommodation."

"It is just possible—though I must tell you, sir, I do not think it is probable—that you might be able to induce the owner of some small craft to run the risk of putting you across; but, as far as we are concerned, it is out of the question. Why, sir, I can tell you this, if we had a boat running this afternoon, I could fill every berth thrice over, and in less than half an hour. What's more, sir, I'd be one of the passengers myself. We've been deluged with applications all day. It looks as if everybody is being scared off the Continent by the news of the plague. I only wish I were safe back in England myself. I was a fool ever to have left it."

While the man was talking, I had been casting about me for some way out of my difficulty, and the news that this awful pestilence had made its appearance in the very city in which we now were filled me with so great a fear that, under the influence of it, I very nearly broke down. Pulling myself together, however, I thanked the man for his information, and made my way into the street once more. There I paused, and considered what I should do. To delay was impossible. Even now Pharos might be close behind me. A few hours more, and it was just possible he might have tracked us to our hiding-place. But I soon discovered that even my dread of Pharos was not as great as my fear of the plague, and, as I have said before, I did not fear that for myself. It was of Valerie I thought, of the woman I loved more than all the world; whose existence was so much to me that without her I should not have cared to go on living. The recollection of her illness brought a thought into my mind that was so terrible, so overpowering, that I staggered on the pavement, and had to clutch at a tree for support.

"My God," I said to myself, "what should I do if this illness proved to be the plague?"

The very thought of such a thing was more than I could bear. It choked, it suffocated me, taking all the pluck out of me, and making me weaker than a little child. But it could not be true, I said; happen what might, I would not believe it. Fate, which had brought so much evil upon me already, could not be so cruel as to frustrate all my hopes just when I thought I had turned the corner and was in sight of peace once more.

What the passers-by must have thought, I do not know, nor do I care. The dreadful thought that filled my mind was more to me than any one else's good opinion could possibly be. When I recovered myself, I resumed my walk to the hotel, breathing in gasps as the thought returned upon me, and my whole body alternately flushing with hope and then numbed with terror. More dead than alive, I entered the building and climbed the stairs to the sitting-room I had engaged. I had half hoped that, on opening the door, I should find Valerie awaiting me there, but I was disappointed. Unable to contain my anxiety any longer, I went along the passage and knocked at the door of her room.

"Who is there?" a voice that I scarcely recognised asked in German.

"It is I," I replied. "Are you feeling better?" "Yes, better," she answered, still in the same hard tone; "but I think I would prefer to lie here a little longer. Do not be anxious about me; I shall be quite myself again by dinner-time."

I asked if there was anything I could procure for her, and, on being informed to the contrary, left her and went down to the manager's office in the hope that I might be able to discover from him some way in which we might escape to our own country.

"You have reached Hamburg at a most unfortunate time," he answered. "As you are doubtless aware, the plague has broken out here, and Heaven alone knows what we shall do if it continues. I have seen one of the councillors within the last hour, and he tells me that three fresh cases have been notified since midday. The evening telegrams report that more than five thousand deaths have already occurred in Turkey and Russia alone. It is raging in Vienna, and indeed through the whole of Austria. In Dresden and Berlin it has also commenced its dreadful work, while three cases have been certified in France. So far England is free; but how long she will continue to be so, it is impossible to say. That they are growing anxious there is evident from the stringency of the quarantine regulations they are passing. No vessel from any infected country—they do not limit it even to ports—is allowed to land either passengers or cargo until after three weeks' quarantine, so that communication with the Continent is practically cut off. The situation is growing extremely critical, and every twenty-four hours promises to make it more so."

"In that case I do not know what I shall do," I said, feeling as if my heart would break under the load it was compelled to carry.

"I am extremely sorry for you, sir," the manager answered; "but what is bad for you is even worse for us. You simply want to get back to your home. We have home, nay, even life itself at stake."

"It is bad for every one alike," I answered, and then, with a heart even heavier than it was before, I thanked him for his courtesy and made my way upstairs to our sitting-room once more. I opened the door and walked in, and then uttered a cry of delight, for Valerie was at the farther end of the room, standing before the window. My pleasure, however, was short-lived, for on hearing my step she turned, and I was able to see her face. What I saw there almost brought my heart into my mouth.

"Valerie!" I cried, "what has happened? Are you worse that you look at me like that?"

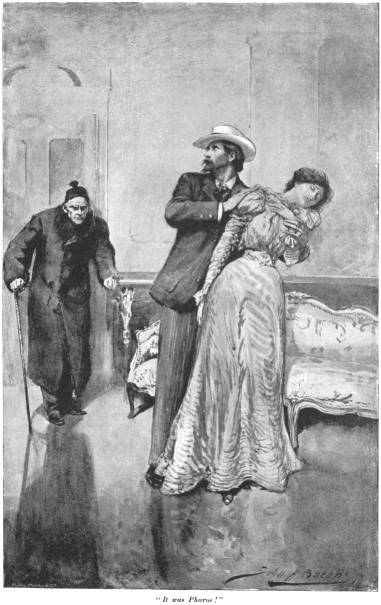

"Hush!" she whispered; "do not speak so loud. Cannot you see that Pharos is coming?"

Her beautiful eyes were open to their widest extent, and there was an air about her that spoke of an impending tragedy.